The major restoration work

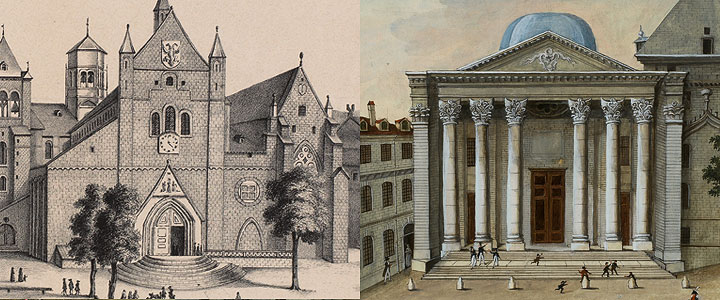

Of the cathedral built in the 12th and 13th centuries, some would say that little is left - but others would contend that a lot is still here. Ravaged by fires or even all-out assaults several times, St Peter’s Cathedral underwent major repair work on numerous occasions over the centuries, altering its outward appearance.

In 1430, a big fire hit the south tower and destroyed the spire, which was replaced with a small belltower. In 1441, the north wall of the nave collapsed, crushing part of the cloisters and the room above them, and bringing down the vaulted ceiling of the nave as it fell.

As far as the interior is concerned, the opulence of the multicoloured decorations, which culminated in Konrad Witz’s retable in 1444, was swept away by the Reformation, which also led to galleries being installed in the aisles and the Chapel of the Maccabees being divided into floors, where the Academy’s lessons would be held.

The Greco-Roman front steps

It was in the 18th century, a time when many prestigious buildings were erected in Geneva, that the decision was finally taken to deal with the cathedral’s weak foundations, due to which there had long been a threat that the façade might collapse. Indeed, the re-use in the 12th century of poorly suited foundations dating from the 6th-century church explains the chronic instability of the north-west corner of the temple, and above all of the lateral façade that overhangs the former cloisters. In 1749, the temple was closed due to the danger of collapse, the first time its role in divine service had been interrupted since it was first built. The work lasted from 1752 to 1756, during which time the cathedral remained partially open but could not host large gatherings such as meetings of the General Council or the Promotions. The design chosen was that of Benedetto Alfieri (1699-1767) from Turin, the architect of the Duke of Savoy, who gave the façade a Greco-Roman portico modelled on the ones being built in Rome and Paris at the time. The former foundations of the façade were completely surrounded by a solid block that acted like pincers, and is still visible today at the archaeological site. The architect consolidated the nave with elegant inverted flying buttresses (these were replaced in the late 19th century with oversized abutments), and put a network of metallic tie rods into the superstructure that guaranteed its stability. To finance this work, a system of renting seats in the restored cathedral was introduced in 1751. The seats were divided into three classes. The best ones were reserved for the Lordship, the Ministers, wealthy foreigners, lawyers, doctors, and so on. 1200 seats were allocated in this way for nine years, and could then be passed on or sold. In addition to this, an appeal for donations was made. Such was the enthusiasm for the cause that the city raised more money than was needed, enabling an organ to be purchased. On 5th December 1756, the temple was officially opened for services in a big ceremony.

Rebirth of the Chapel of the Maccabees

In 1878, a team set about completely restoring the Chapel of the Maccabees, which lay in ruins. Since the Reformation, it had served as a classroom for the Academy, then as a storage room for salt and powder. It was in such a dilapidated state in the late 18th century that there was even talk of demolishing it. The handful of frescoes that remained were uninstalled (a technique that was first tested in French-speaking Switzerland) and put in the care of the Museum of Art and History. The restoration work was completed ten years later, after being led by the City architect Louis Viollier (1852-1931) in accordance with a plan proposed 30 years earlier by Jean-Daniel Blavignac, staying true to historical accuracy. Viollier made the project a “complete work of art”, in line with Neo-Gothic tastes, combining painting, sculpture, woodwork, ironwork and ceramics. The vaults were decorated with frescoes by Gustave de Beaumont, faithfully reproducing the original paintings that depicted a celestial concert.

The changing profile of the cathedral

Construction work on the cathedral itself began in 1884. The entire exterior was in very bad condition, and would form the main subject of the works. Viollier began by overhauling the structures, not least by replacing the flying buttresses of the nave, installed by Alfieri, with enlarged abutments topped with pinnacles. The north tower, which was in a terrible state of repair, was almost completely rebuilt, and made taller. Viollier opted to use calcareous stone rather than the molasse used originally, which he deemed too weak. He drew criticism from many over the general aesthetic of the top of the tower, which was very different from the old one. Between the two towers, a new spire, modelled on the old medieval spire (which had been replaced with a small belltower after several fires), was built, consisting of a metallic armature and covered with copper.

Inside, the 6 new stained glass windows in the choir were magnificent copies of originals from the Middle Ages. What was left of the old stained glass windows would now join Konrad Witz’s retable in the Museum of Art and History.

The monument to the Duke of Rohan was restored and topped with a new statue. The lateral galleries, which had been added over the years so that as large a congregation as possible could fit into the cathedral, had already been taken out several decades earlier.

The archaeological site

In 1977, the cathedral closed its doors for four years, in order to undertake a huge restoration job aimed at completely renovating the cathedral’s interior and, by so doing, extracting from its entrails a long page in Geneva’s Christian history. The digs were conducted in a systematic manner, led by the archaeologist Charles Bonnet, not just in the basement of the cathedral, but in the immediate vicinity of it as well. Several areas were specially landscaped, and, together with the constantly updated museographical techniques, amount to one of the most enormous archaeological sites in Europe, north of the Alps. The archaeological pathway thus begins in the 3rd century CE and ends with the construction of the current cathedral, undertaken in the 12th century (www.site-archeologique.ch)

The Foundation of the Keys of St Peter

This vast renovation undertaking, which continued after the cathedral reopened with the gradual restoration of the building’s exterior, was led by the board of the Foundation of the Keys of St Peter, created in 1973 by the National Protestant Church of Geneva and by the parish of Saint-Pierre Fusterie, to oversee the conservation of the cathedral. The works were jointly financed by the Confederation, the Canton and the City of Geneva, and also by the funds raised on the feast days of the Keys of St Peter in 1976 (renewed in 1982), which brought more than 250,000 people to the Old Town to enjoy an entertainment programme organised by ‘Genevese’ Geneva and ‘international’ Geneva. The Foundation of the Keys of St Peter is still playing its essential role today, ensuring that this monument is promoted and conserved.

At the heart of Geneva’s Old Town, the cathedral is now very much part of the city’s spiritual and cultural furniture. Besides the cathedral and its archaeological site, since 2005 the International Museum of the Reformation (‘Musée international de la Réforme’, www.musee-reforme.ch) has also been nearby, located in the Mallet house built in the early 18th century on the site of the cathedral’s former cloisters. Set slightly further back from it, the Calvin Auditorium, in which the reformer once taught his pupils, completes the set of buildings.