The recent history of st peter’s: religious strife makes way for social unrest; secularism gets the better of religiosity

A golden century

The 18th century was a golden age for Geneva. The peril on the borders disappeared. The city grew larger, and numerous splendid residences were built (notably the Mallet house on the site of the cloisters at St Peter’s, which were knocked down); the former refugees prospered, with many of them becoming rich bankers who even financed the king of France!

In 1735, celebrations were held to mark the bicentenary of the Reformation. The Calvinist doctrine was somewhat softened, but the spirit of it lived on, as did faithfulness to the Holy Scriptures and a strong attachment to the Reformation. But whilst faith remained very strong and was a unifying force, the emergence of a stratum in society with the “nouveaux riches” created divisions. The new bourgeois households started to usurp the power that had been enjoyed by the ‘aristocrats’. The middle classes began their power grab, by strengthening the role of the General Council, which became their fiefdom. These developments also awakened the popular classes, however, who, in turn, laid claim to a degree of influence befitting their numerical superiority.

The Revolution

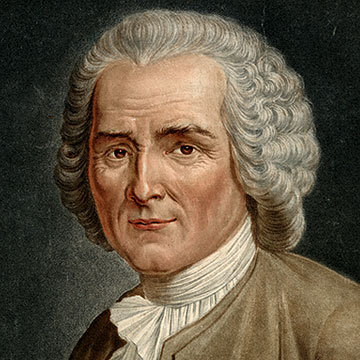

In 1792, the old regime was in its death throes in Geneva. The traditional social order, its system of values and even religion - the entire edifice was crumbling. There were increasingly large numbers of Catholics, and universal, or quasi-universal, suffrage had become a reality. The meetings of the General Council, which had now become the Sovereign Assembly, still took place at St Peter’s, but nothing much happened at them anymore; the real power lay in the political clubs in Place Bel-Air. In 1794, the ‘revolutionary’ government, relatively different from that of 1792, was overthrown in turn by the most ardent faction, who, just as in France, appointed a revolutionary tribunal, which sentenced some of the ‘aristocrats’ to death; ultimately, eleven of them were executed. The number of places of worship was cut, as was the number of services; the revolutionary clubs demanded that the ‘Declaration of the rights and duties of man in society’ be displayed at the places of worship, a sign of the strong influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. At St Peter’s, the tomb of the Duke of Rohan was dismantled; the cathedral became primarily a site of secular ceremonies and elections; there was talk of rechristening it the Temple of Laws during a ceremony intended to celebrate the bonds between Geneva, revolutionary France and the United States of America.

Re-annexation of Geneva to France

People were increasingly concerned by rumours that Geneva would soon be re-annexed to France, and this duly happened in April 1798, when Geneva was stormed by a force of 1600 men. It became the administrative capital of the French ‘département’ of Le Léman, for fifteen years. The General Council did not survive these developments. During this period, St Peter’s served as a venue for ceremonies honouring France. It was here that the prefects preached their sermons. Even the festival of the Promotions now took on a bitter taste for the locals, for it was presided over by the prefect. In 1801, the Concordat reestablished peace between France and the Church of Rome (the two had fallen out due to the Revolution), and also guaranteed the rights of religious minorities. These newly-restored good relations between the civic and religious authorities meant that worship could take place at St Peter’s again, after an eight-year absence. The cathedral once again became a meeting place and a place for the populace to come together around their pastors. Moreover, this period of annexation reaffirmed the right of city acquired by Catholicism, to whom the Temple of Saint-Germain was conceded. In 1810, Geneva’s Protestants got wind of measures taken by the prefect to try to make St Peter’s a place of worship for Catholicism. The Faculty of Theology was therefore transferred to the Chapel of Portugal, which was equipped with a furnace for the winter, so as to improve occupancy of the premises.

Geneva enters the Swiss Confederation

At the moment when Napoleon’s army was defeated, Geneva was liberated on 30 December 1813 by the Austrian troops, and, the next day, after the prefect had left once and for all, a provisional government led by the former unionist Ami Lullin proclaimed the Restoration of the Republic of Geneva, and managed to get the Genevans to adopt a constitution that did away with the General Council, arguing that the Confederates were demanding this in order for Geneva to be admitted. On 1st June 1814, Swiss troops (made up of contingents from Fribourg and Soleur) disembarked at Port Noir in Geneva, then, in July, began negotiations over Geneva’s entry into the Confederation. Despite the fears of Swiss Catholics regarding ‘Protestant Rome’ and the turmoil it had known in the 18th century, Geneva’s reattachment to Switzerland took effect on 19 May 1815. The territories granted to Geneva in order to open it up led to a sizeable Catholic population, who resided in the nearby rural areas that had hitherto belonged to France or Sardaigne. The new Constitution granted the same rights to Catholics as to Protestants. Tensions between the two faiths lived on, however. There were even tensions within the Protestant faith, with some deeming that the religion had moved too far away from the doctrine of Calvin, and founding the church of the Réveil (the ‘Awakening’) as a result.

The Constitution of 1847

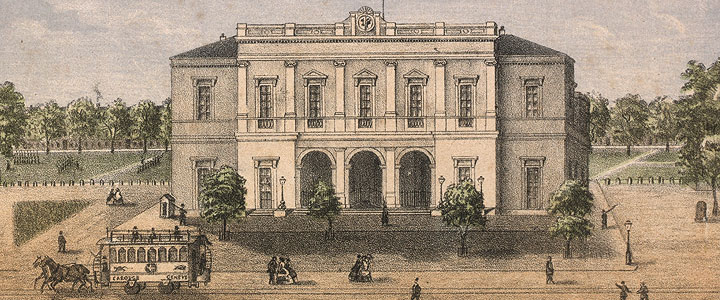

Geneva’s new political construction was fragile, and would soon come under an assault - in a democratic sense - by James Fazy and the burgeoning radical party. The Constitution of 1847, dictated by Fazy and replacing the one from 1842 while it was still in its infancy, re-established the General Council, a set of Genevan electors, which it put in charge of appointing magistrates. It was to do its work at St Peter’s Temple. In May 1847, he was one of the State Councillors elected in this way. But this renaissance couldn’t last, the forms had changed, and the multiplicity of faiths and universal suffrage had to be taken into account. Furthermore, the authorities of the Protestant Church took umbrage on seeing the temple used in a disrespectful way to host elections, particularly given that they took place on Sundays, thereby causing maximum disruption to the original vocation of the building. The State Council and the Administrative Council of the City were convinced of the need to construct a building to house the General Council. A round of public borrowing was launched and met with a good response, not least by Protestant circles in Geneva. In November 1855, the new Electoral Building was inaugurated. But the elected members of the executive would go on to preach a sermon in the cathedral on the day they took up office - a tradition that has continued right up to the present day.

Restructuring of the Reformed Church

In 1842, when the Constitution was revised, the reformed Church took on the name of the National Protestant Church. It would henceforth have to be organised democratically, in accordance with the prevailing ideas of the time - those of James Fazy and the radical government. The Constitution of 1847 would accentuate even more this alignment of the Church with the political institutions: management of the church passed from the Pastors to a Consistory, a sort of Church Parliament, appointed by the electors and with most of its members being secular citizens. Calvin’s Church of the Clergy became a Church of the People. Some traditionalists regretted this change, and in 1849 they founded the free evangelical church. The Catholics were still in the majority, making up more than half of Geneva’s population in the late 19th century.

The Separation of Church and State

The Fazyist government fought against the influence of the churches, and sought to gradually make the big ceremonies and occasions more secular, not least the Promotions. From 1856 onwards, the Promotions were no longer celebrated at St Peter’s, but in the brand new electoral building. Secularisation, the separating of the temporal and the spiritual, was a battle waged by the opponents of the church but also by certain fervent reformers, who felt that the Church ought not to endanger the State. After several aborted attempts, a policy of removing funding from religions was voted through on 30 June 1907 by the population of Geneva, by a slender majority. St Peter’s was at that point ceded by the City to the National Protestant Church, with the sole proviso that “the State and the City of Geneva shall continue, as in the past, to be able to make use of the temple of St Peter for national ceremonies”. In reality, the only thing that really remained was that, with the arrival of each new legislature, the Council of State was installed, and on that day, the Council would preach a sermon on the Bible in the cathedral, where, in centuries gone by, all the important events of civic life had taken place.